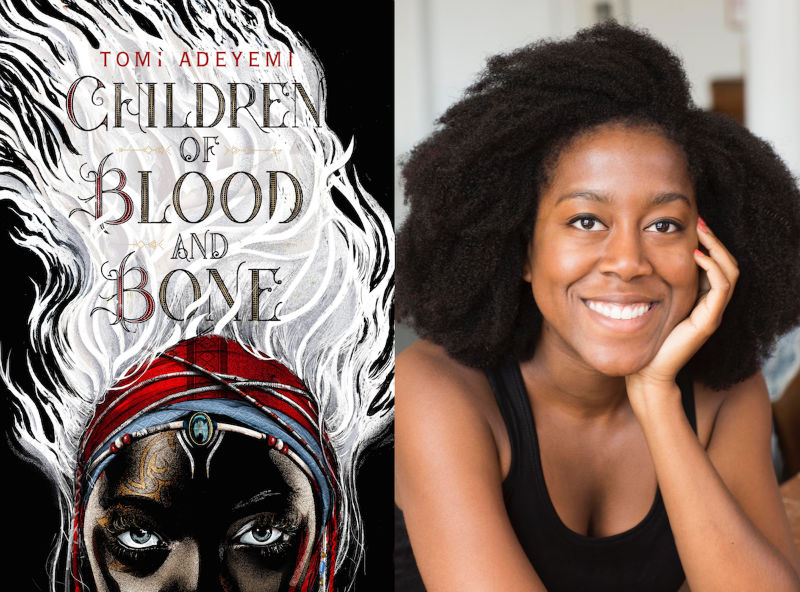

Book Review: Children of Blood of Bone by Tomi Adeyemi

Fantasy is a genre that, frankly, lost my interest a while ago. After Tolkien came onto the scene and introduced the epic hero’s journey, many copycats popped up, and it seemed to me that every fantasy book I read was the same. The young, white, man hero living a simple life has a quest thrust upon him by an older white man wizard and has to undergo a dangerous journey to save [insert one here: the girl, his hometown, the country, the world, or himself]. He encounters obstacles, collects sidekicks and friends, probably falls in love with an irresistible elf, completes his quest, and returns home a hero and a changed man.

The hero’s journey became something for men, and mostly white men, and it just got boring for me. Then, authors like N.K. Jemisin, Nnedi Okorafor, and Tananarive Due came onto the scene and changed my mind. I learned that fantasy can be so much more than white men on an epic journey. Sure, the epic journey is still prominent, but now, we’re getting more interesting and diverse worlds, deeper characters, and heroes who aren’t white or men.

Which brings me to Tomi Adeyemi and Children of Blood and Bone. Adeyemi isn’t the first to write a book like this [see authors above], but she has successfully distilled Black girl magic into a novel for teens that weaves Nigerian culture and history into its deft storytelling. She builds a magnificent world touching on all the senses and explores social themes like men’s control over women’s bodies (and white control over black bodies), state-sponsored killing, community building, identity struggles, allyship, friendship, bondage and slavery, gender roles, and acknowledging, questioning, and re-evaluating the values with which you’re raised and redirecting them (or not). Adeyemi channels the magic and worldbuilding of Black Panther and the social justice themes of Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give into a 525 page breathtaking YA fantasy that will sweep you off your feet.

Children of Blood and Bone is the story of Zélie Adebola, a teen who definitely does not have a mundane, simple life and who has seen her share of trauma, who has a quest thrust upon her by an older ex-maji woman to undergo a dangerous journey to save magic. With the help of her brother, Tzain, and a rebellious princess, Amari, Zélie encounters obstacles, has to outsmart the crown prince, Inan, who has his own past haunting him, and has to learn to believe in herself to complete her quest and save magic. Sound familiar?

Here’s the difference: Adeyemi takes the epic hero’s journey structure and twists it, drawing on her Nigerian roots to populate the world of Orïsha with huge panthenaires, dashikis, geles, jollof rice, rich colors and smells, unique architecture, and the language of Yoruba. She completely rejects the Western/European fantasy framework to create a world full of only Black people (and their ryders, of course) and a story with a focus on Black women, and through this, she thoroughly dismisses white maleness as the default mode of fantasy and gives us a story that celebrates Black culture and Black women.

I LOVE that this story centers two strong Black women who approach their individual journeys in starkly different ways and who come from completely different backgrounds and levels of privilege, but they’re still able to learn from each other and to grow together. Zélie is a divîner, the child of a maji mother who was killed in the Raids perpetrated by Amari’s father, who destroys Zélie’s home; Amari is a privileged princess who comes with her own personal trauma.

In Orïsha, light brown skin denotes high rank and power, while dark brown skin and white hair denote the lowest rank – divîners. This colorism manifests in the royal family’s shame of past mixing with maji, which is seen in Amari’s slightly darker skin, and in the way the monarchy treats divîners as inhuman slaves. Amari is able to reject her upbringing and use her place of privilege to help divîners, although at the beginning, Zélie relentlessly chastises Amari for being a “privileged princess.”

Zélie, on the other hand, was born a divîner and always lived a life of oppression at the hand of King Saran, Amari’s father. As the story develops, Zélie and Amari learn more about each other and grow together, Zélie understanding more about Amari’s personal trauma even in her place of privilege, and Amari understanding more about how her father’s actions have oppressed not only Zélie, but all divîners. Both of these women show strength, albeit in different ways, and Adeyemi isn’t afraid to portray the intimacy of their friendship, showing how women support and protect each other and lift each other up in beautiful ways.

I also loved Inan’s journey and how Adeyemi used his character to shed light on the struggle of identity – of reconciling who you really are with how society views you, and your past with your future. Inan is driven by duty to his country, self loathing, and both fear of and wanting to please his father. He consistently struggles with who he is and how he can best serve his country and how those things conflict with what he really wants. His and Amari’s struggles directly parallel the identity struggles of people of color, who must reconcile who they are with how society views them.

Parallels to the real world like this abound in this novel. The way Zélie’s and Amari’s bodies are physically dominated and violated by men parallels the way women are treated; the state-sponsored killing of the maji and the way the guards treat the divîners as less than human parallels police violence against people of color; the divîners’ being sent to “the stocks” and forced into slavery parallels our past and modern day prison system; and Inan’s and Amari’s struggles with evaluating the values they were raised with, acknowledging those values are harmful, and finding ways to overcome that parallels the struggles of allyship. Adeyemi tackles racism, colorism, police violence, slavery, state-sponsored violence, the prison system, and gender roles at one fell swoop.

The characters in this book are just as deeply rooted and complex as the social justice themes. Inan in particular has a moral struggle for the ages, code switching and re-evaluating his actions at every turn. His intentions begin as sinister, then as he gains experience, he truly tries to be better, all for his country. Amari overcomes personal trauma, an abusive childhood, and self worth issues to become a great ally to the divîners, all while putting up with Zélie’s constant badgering and belittling. And Zélie rises up from a poor, oppressed background and endures great adversity and gruesome physical violence to embrace her abilities and lead the resistance.

As complex and morally diverse as the characters are, so are their tactics. Amari is the peacemaker, always trying to broker deals between the oppressed and the oppressors; Inan is the manipulator and gas lighter, convincing the oppressed they are just as wrong as their oppressors and tone policing them into submitting; Zélie is the resistor and warrior, fighting before thinking and using violence to fight violence. Zélie never thinks about changing minds, only about destroying the monarchy. Amari, on the other hand, being a princess, prefers changing people’s ways of thinking over violence. If you read critically enough, you may see Adeyemi is making a statement about needing diverse tactics to successfully resist an oppressive regime.

In many ways, this book can be seen as a general allegory for the struggles of marginalized groups. Of course, Black struggles are prominent, but glimpses of queer issues, the struggles of oppressed religions, and gender oppression also come through. The king’s aversion to the maji and the way people talk about them is akin to the way people talk about queer folks. Statements on homophobia and queer struggles can certainly be gleaned from this narrative, down to the fact that divîners are called “maggots,” which can be seen as a reference to a similar-sounding queer slur.

The maji also observe their own religion, and the pockets of divîners who still practice are forced to do so in secret enclaves hidden away from the rest of the world so they aren’t raided and killed while doing so. But of these deeper themes, gender is the most obvious. While women are magically and physically powerful in this world, men still dominate women’s bodies and the power structure, and they gas light and manipulate at every turn. One of the most disappointing things for me was that there was definitely a male/female dynamic; however, agender, non-binary, and people of other genders were not represented.

Children of Blood and Bone is daring, but it’s not perfect. It has some of the pitfalls I tend to see in YA novels, mainly some unnecessary romance and Zélie incessantly berating herself. I didn’t find the multiple POVs overwhelming as some other reviews suggest; however, they were a bit repetitive at times, following characters who are physically together, thus providing unneeded viewpoints, and rehashing events that just happened. I also didn’t mind the characters’ opinions and viewpoints changing a lot throughout the novel, because that’s what happens with teens.

In the end, this *is* a teen novel, and since I’m not the target audience, of course parts did not appeal to me. But I still really loved this book. The magnificent worldbuilding is immersive, the way Adeyemi weaves social issues and Nigerian culture into the storytelling is deft, the characters were relatable and real, and the plot is enthralling. I was enraptured from the start and never wanted to put this book down. Even after I was done, I wanted to pick it right back up and immediately read it again.

If you loved the worldbuilding and representation in Black Panther, particularly the Dora Milaje, and if you love the magic system and sprawling world of Harry Potter, you will love this book. If you love N.K. Jemisin and Nnedi Okorafor, you will also love this book. I’m so happy Tomi Adeyemi shared her story with us. With a debut novel like this, she’s bound to take the fantasy world by storm.

You can support us by ordering any of the books we mention on our blog, our podcast, or anywhere via our Place a Special Order form or by calling the store. We will even ship directly to your home. If you like our store and our content, the best way to show us is by buying something!

For more book discussions, book lists, and to see what our book clubs are reading, join our Goodreads discussion group.